The most controversial section of Ringway 2, and the one over which the most visceral battles were fought between planners and the public. A sudden and very messy end was the fate of the much-hated motorway from Eltham to Wandsworth.

While the northern side of Ringway 2 would be the North Circular Road itself, the Southern Section wandered far from the South Circular in search of a route suitable for a motorway. As a result, the line passed through through prosperous and peaceful suburbs whose residents had no desire to see their surroundings torn apart by an eight-lane motorway.

Many of the Ringways-era proposals were carried over from older plans, but the south side of Ringway 2 was very different. It had been the intention since the 1930s to upgrade the South Circular to become part of the "C" Ring Road, but when the time came for the Greater London Council to actually do it, the South Circular was beyond help, and this became the first route the GLC created from scratch.

For a Council committed to building a vast network of urban motorways, the GLC proved worryingly inept - irritating the Borough Councils, alienating the public at every turn, and eventually rushing their plans out at the very last minute with no time for consultation. No wonder this was among the most hated of all the motorway plans.

For all the controversy, the underlying idea wasn't so objectionable. Ringway 2 would open up access to a huge sweep of inner South London that was (and remains) difficult to reach by road. It provided a terminus for the M23, so that motorway wouldn't continue its highly destructive journey further inwards. And the GLC weren't completely insensible to the difficulties of building a motorway through the suburbs: their plans would have allowed long lengths to be roofed over where it ran below ground level, hiding it from view, though that was something they thought might happen years after it had been built. The only sections to be put underground at the outset would be where it ran through parks and sports fields, with the motorway emerging into the open air to pass houses, schools and shops.

Outline itinerary

Continues from Ringway 2 Eastern Section

A2(M) (Falconwood Interchange)

A20(M) (Dutch House Interchange)

A2212 Baring Road and Verdant Lane

A21 Bromley Road

Worsley Bridge Road

A214 Elmer's End Road

Parkway E

A215 South Norwood Hill

A23 London Road

M23 (Streatham Vale or Delta Interchange)

A24 High Street Colliers Wood

A3 and Ringway 2 Clapham-Wandsworth Link

Continues to Ringway 2 Western Section

Cost summary

| Property acquisition (1970) | £56,300,000 |

| Rehousing (1970) | £14,300,000 |

| Construction (1970) | £132,300,000 |

| Environmental works (1970) | £8,715,000 |

| Total cost at 1970 prices | £211,615,000 |

| Estimated equivalent at 2014 prices Based on RPI and property price inflation |

£2,399,427,856 |

See the full costs of all Ringways schemes on the Cost Estimates page.

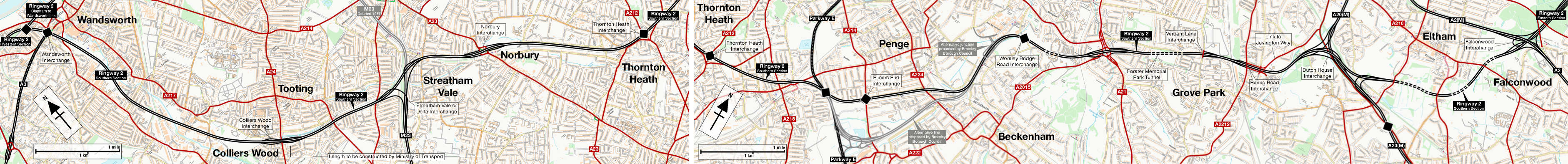

Route map

Scroll this map horizontally to see the whole route

Route description

This description begins at the eastern end of the route and travels west.

Kidbrooke to Beckenham

Commencing on the A2(M) at Falconwood Interchange as a direct continuation of the Ringway 2 Eastern Section, the route would begin by turning south-west through Avery Hill, passing beneath Mottingham Golf Course in a cut-and-cover tunnel. It would briefly run parallel to the railway line between Lee and Mottingham before reaching Dutch House Interchange, a major junction with the A20(M) where three levels of flyovers would stack up at the foot of the hill below Eltham Palace.

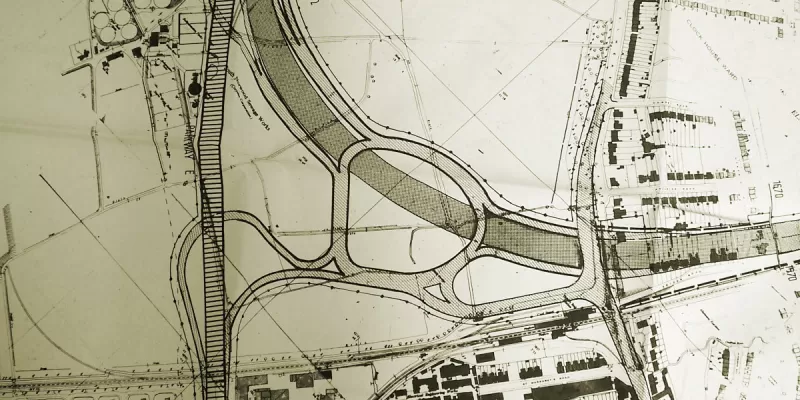

A double-bend would bring Ringway 2 to the suburb of Grove Park, with junctions provided on both sides of the railway line. At the A2212 Baring Road, west-facing sliproads would lead to a link from Jevington Way and the A20; five lanes in each direction would then cross the railway to east-facing sliproads at the junction of Verdant Lane and Whitefoot Lane. The motorway would then run under Forster Memorial Park in another cut-and-cover tunnel, then pass between Cotton Hill and Brockman Rise. Every house between those streets would have been demolished, with the motorway placed in a walled cutting, so the remaining houses would have looked out across a deep trench carrying eight lanes of traffic. At the A21 Bromley Road, a three-level junction would be provided, with the A21 passing through a single-carriageway underpass below the roundabout.

The motorway would continue west through the grounds of Sedgehill School to reach another junction at Worsley Bridge Road, before curving southwards through the HBOS Playing Fields to join the west side of the Mid Kent railway line at New Beckenham station. At Beckenham, it would turn south-west to join the west side of the Crystal Palace line, requiring the demolition of everything on the south side of Mackenzie Road, to reach another local junction at the A214 Elmer's End Road.

Beckenham to Wandsworth

The motorway would continue along the west side of a now-closed branch railway between Birkbeck and Norwood Junction just to the north of Regina Road. Another major interchange would be formed here, this time with Parkway E. On the next section, there were no convenient railway lines to follow, so Ringway 2 would push a new and highly destructive line through South Norwood, passing through the historic Stanley Halls and cutting against the grain through houses between Selhurst Road and Holmesdale Road. Turning west, the motorway would clip off the corner of the north stand at Selhurst Park football ground to reach the junction of the A212 Grange Road and Whitehorse Lane, which would become the next interchange - this time destroying one end of the shopping district at Thornton Heath.

Running along the north side of the B266 Thornton Heath High Street, the motorway would then pass through what is now a Tesco superstore before joining the east side of the Brighton Main Line railway and running north-west, requiring the demolition of all the houses on the south side of Norbury Avenue. The next junction would be at Norbury, where a roundabout interchange would provide connections to the A23 London Road.

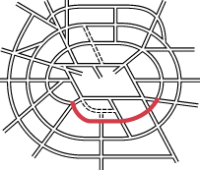

Ringway 2 would continue along the north side of the railway, claiming all the houses on the south side of Ellison Road, before curving west through what is now Homebase and the houses on Carnforth Road. Here, in the midst of a complex railway junction, a major free-flowing interchange would form the northern terminus of the M23. In official documentation it is known variously as Streatham Vale Interchange or the Delta Interchange - the latter because it was triangular in shape. The motorway would then continue west, now on the south side of the Tooting to Wimbledon railway line, and again claiming whole streets of Victorian terraces on Ashbourne Road and Lyveden Road. Another local junction would connect to the A24 High Street Colliers Wood.

Beyond the A24 the streets and houses give way to the Wandle Valley and the vast Lambeth Cemetery. Ringway 2 would skirt the southern edge of the cemetery before turning north along roughly the line of the River Wandle itself, pushing a new line through low-rise industrial development. At Earlsfield the motorway would cut through several more residential streets in the vicinity of Acuba Road before finding an easier route through a series of playing fields into St George's Park. Much of this length through the low-lying ground of the Wandle Valley would be elevated, with concrete viaducts carrying eight lanes of traffic at first floor level.

North of there, at Wandsworth, the motorway would turn westwards, heading for the railway from Waterloo towards Richmond. A final major interchange would be located just west of Wandsworth Town Centre close to Putney Bridge Road, where the Clapham-Wandsworth Link would join from the east and the upgraded A3 would join from the west. No plans for this interchange seem to have survived, but planning officers from Wandsworth Borough Council saw drawings of it in 1967, and their notes describe it as "particularly large". They mention substantial areas of empty, sterilised land in the middle of it and note that the GLC proposed a whole new pattern of local roads surrounding it. The implication is that the whole western part of Wandsworth would be virtually unrecognisable, reconfigured around a vast motorway interchange complex.

Beyond Wandsworth, the route would flow on to Ringway 2's Western Section.

No place for a new motorway

When the GLC was created in 1965, they took over planning for a London-wide motorway network, but in South London all they inherited from the former London County Council was the aspiration to upgrade the South Circular Road. The demand for orbital travel that was projected between London's suburbs, and the nature of the existing South Circular, meant that plan was almost immediately abandoned. The GLC needed a new route entirely.

Eventually, they found it. In several stages, they produced plans for a complete replacement of the South Circular, and in November 1968 announced it would be built as a four-lane motorway. The route from the A13 near Beckton to the A4 at Chiswick was announced in stages between 1967 and 1969.

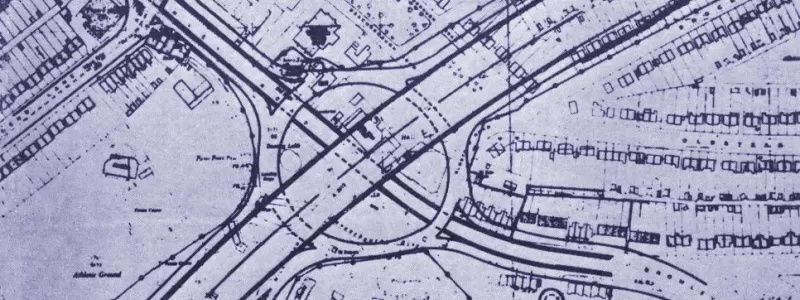

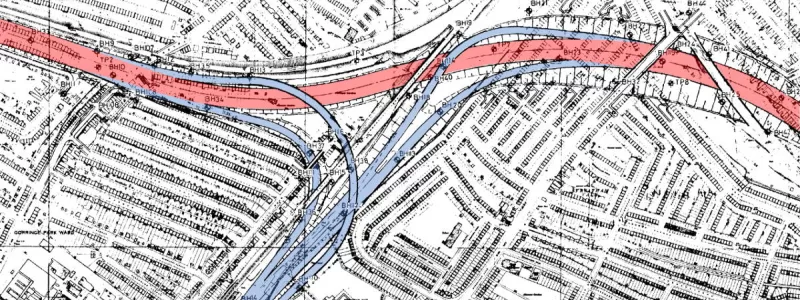

The final part, from Norbury to Falconwood, was the most difficult, for the simple reason that there was no good or obvious alignment for a motorway between those points at all. Over a period of three years the GLC's engineers plotted out and evaluated 29 alternative lines. These were progressively whittled down until the last few were presented to the Planning and Transportation Committee, who selected their preferred one in July 1969. This was, within a matter of days, made public as the final and official route for Ringway 2.

It is not normal practice to decide the route of a motorway in total secrecy and to only present one single option for consultation. It is not normal practice to exclude not only the public but all other government bodies and stakeholders until the point at which you've drawn up detailed engineering plans of your one route option. But the GLC's engineers and elected members rather innocently thought they were helping by adopting this unusually paternalistic approach. By publishing one single route they hoped to minimise uncertainty, and they immediately offered full market price to anyone on the line of the road who wished to sell their home, so nobody was unable to move. They hoped it would make things simpler.

The public response was not quite as positive as they might have hoped - of which, more later - but perhaps nothing illustrates just how effectively the GLC unwittingly made enemies better than its entirely avoidable stand-off with Bromley Borough Council. Ringway 2 passed through Bromley borough between Elmer's End and Grove Park, but by May 1969 the council had yet to hear anything at all about this eight-lane motorway. The GLC was making decisions about planning in their borough in total secrecy. Bromley's Development Committee threatened to escalate the matter to the Minister of Housing and Local Government to force the GLC to let them in on the planning process, but still the GLC declined to involve them. They had to wait until the route was made public in July 1969 to see it.

The formal consultation, when it began, was the first time the boroughs and the public had seen the route, and it had a remarkably short timeframe of just a few months so that it would end before the start of the GLDP Inquiry, giving little time for anything to be discussed or evaluated in meaningful detail. Frustrated, Bromley proposed an alternative route around Beckenham, following a different railway east of the GLC line, which they thought a better fit for their borough. The GLC appeared to take no notice, so in April 1970 Bromley took the remarkable step of publishing it themselves, beginning their own public consultation exercise, and obtaining permission from the Minister to buy houses on the line of their motorway route just as the GLC were buying up houses on the official one.

Among the advantages of Bromley's route were the demolition of fewer houses that were generally older and harder to modernise, more space for an interchange with Parkway E, cheaper land and construction costs, and the relocation of an interchange from Worsley Bridge Road to Kangley Bridge Road, meaning that traffic heading to and from the motorway would travel through an industrial estate, not a residential area.

The GLC remained, remarkably, almost totally unresponsive to this or any other criticism, insisting that the GLDP Inquiry was the place for objections to be raised. Finally, in late 1970, they weakened under the barrage of inter-council correspondence, and grudgingly admitted that Bromley's line was indeed superior in almost every respect. But - oh dear - it was too late to amend the official route of Ringway 2 because the GLDP Inquiry had started, so instead it was submitted to the Inquiry panel as an alternative option.

Bromley's reaction, if they responded at all, was not kept on file.

A very public uprising

The decision to build a motorway through South London suburbia was always going to attract controversy, but the GLC's gormless handling of the planning process managed to alienate even their closest allies. Protest and opposition groups were forming across the city, but in South London the fight against Ringway 2 was slightly different because it was brand new. Many of the GLC and Ministry's road proposals were upgrades to existing roads or iterations of plans that had existed for decades, and in some places land was even set aside for them. The south side of Ringway 2, on the other hand, was a complete shock to thousands of people who had no reason to think their street or neighbourhood would ever lie in the path of a motorway.

It was here, under the shadow of Ringway 2, that the protests first turned political, with MPs addressing mass rallies in the streets of Croydon and Streatham, and local councils pledging to unite against the plans. The leader of Lambeth Borough Council, Geoffrey Manning, made a dramatic statement promising to "whip up" public support against the motorway, concluding with the words "stand by for fireworks".

The GLC, for its part, held public information events at libraries and community centres across South London, and installed a major exhibition at County Hall where the plans could be inspected and Council officers interrogated. Their correspondence file is full of disgruntled attendees complaining that nobody at the exhibition actually seemed to know anything. And it despatched Robert Vigars, GLC Cabinet member and the chair of the Planning and Transportation Committee, to attend meetings of the newly-formed residents' groups and address them, making the case for the new road. Vigars was the man responsible for developing the motorway plans, and as their public face he soaked up much of the opprobrium.

Accounts of these meetings generally describe Vigars attempting to say his piece while a packed hall of angry people drown him out with heckles and jeers. This one, about a meeting attended by 1,500 South London residents, is typical.

"Mr. Vigars said that about 30,000 houses in the London area would have to be demolished to make way for the new motorways.

"But he assured the audience, who constantly interrupted his speech with booing and catcalls, that everyone affected in the scheme, which would be completed during the next 15 years, will be adequately 'taken care of'."

Vigars' own party also had its doubts, at least at the local level. Once plans were announced for the section between Mitcham and Norbury, passing through Streatham Vale, the local Conservative Association wrote to him, referencing the GLC's own slogan.

"[The executive committee] is deeply concerned at the substantial loss (by demolition) of good modern houses and the destruction of a good residential community coupled with loss of amenity, and is convinced that this is not the best way to 'get London moving' or in the best interests of Greater London, and is therefore determined to oppose by all means the present proposals."

The remarkable level of dissent went right the way to the top. Ringway 2 passed through the constituency of Richard Marsh, MP for Greenwich, and wouldn't have been far from his back garden. When he wrote to Robert Vigars about the new motorway, in September 1969, he was also Minister of Transport. He described himself as the only person in London not entitled to have an opinion about Ringway 2, before adding that "it is difficult to hold this position in Eltham and I would find it impossible to maintain it, with or without compensation, if the road encroached upon any more of the delightful countryside between my home and the railway line".

With opposition from every quarter, it can seem almost bizarre that Vigars and the GLC ever thought their motorway might be built. In the end, as the major political parties began to catch up with the public view, Ringway 2's southern section was the first road to lose the backing of both Labour and the Conservatives, effectively killing it off in 1972, a year before the motorways were formally cancelled. The Croydon Advertiser, reporting the news, said that jubilation across South London would be "loud and long".

The trunk road to nowhere

The GLC were responsible for all of the southern side of Ringway 2, except for one small bit. Once it was settled that the M23 would terminate on Ringway 2 at Streatham Vale, the phasing of the various road schemes created a problem. The M23 was due to be built before Ringway 2, which left it with nowhere to go.

To make the plan work, a short length of Ringway 2 was transferred to the Ministry of Transport, so that they would build the section between the A23 and A24 as part of the M23 project. When the rest of the route opened, it would then be transferred back to GLC control. Achieving this was a surprisingly difficult task, and demanded many months of bureaucratic gymnastics in the late 1960s.

Once the transfer was complete, the MOT didn't mess about. In July 1969, while the GLC were still only announcing the approximate route of the Norbury-Falconwood section to a horrified general public, the Ministry published line and side road orders for the M23 scheme, including Ringway 2 between the A23 and A24 - the legal orders that would get the road built and a precursor to sending in the bulldozers. Their plans show the M23 finishing at a free-flowing interchange on a short, isolated length of dual four-lane motorway, which narrowed at each end into a set of sliproads, allowing space for its future continuation. Further progress was then suspended until the GLDP Inquiry had concluded.

This was the situation in 1973, when politics caught up with public opinion and the GLC dumped all its motorway plans. Ringway 2 was instantly dead - with the notable exception of one orphaned stretch between the A23 and A24. The Department of the Environment (as the MOT had become) were left holding the baby. They had a major trunk road scheme at a late stage of the planning process, but if they allowed it to proceed, the result would be a major London radial motorway terminating on two stub-ends of motorway that would never, now, lead anywhere at all. It was a complete white elephant of a scheme and clearly a re-think was needed. Reports were written and heads were scratched.

For several years, indecision reigned, until eventually the DoE did the only thing it really could do: the legal orders for Ringway 2 and the Delta Interchange were withdrawn, stalling progress on the M23 for good.

Picture credits

- Route map contains OS data © Crown copyright and database rights (2017) used under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

- Archive photographs of M23 interchange architectural model are used under licence from London Metropolitan Archives, City of London (Collage record numbers 247788 and 247786).

- Map showing approximate route of Ringway 2 taken from "Ringway 2: Norbury-Falconwood" (1969), GLC.

- Plan of A21 interchange taken from "Here's the Secret M-Way Map and all the Details", Lewisham Mercury, London, 4 December 1969.

- Photograph of River Wandle at Earlsfield taken from an original by Marathon and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- GLC map showing route options is extracted from GLC/DG/AR/6/093.

- Bromley Borough Council layout for Parkway E interchange extracted from HLG 159/2183.

- Photograph of Robinson Road taken from an original by Ian S and used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Photograph of Robert Vigars appeared in the Daily Telegraph, 18 July 1969.

- Portrait of Richard William Marsh, Baron Marsh by Walter Bird, bromide print, 4 May 1965, NPG x186499 © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used under this Creative Commons licence.

- Plan of Streatham Vale interchange adapted from "Proposed Scheme" plan sheet F69/523/1 produced by Ministry of Transport SERCU, undated.

Sources

- Intention to upgrade South Circular since 1930s: Bressey, C. and Lutyens, E. (1938). Highway Development Survey 1937: Greater London. London: Ministry of Transport.

- Route, Falconwood to Norbury: GLC/DG/AR/6/093.

- Route, Colliers Wood to Wandsworth: "London's Motorway Network Takes Shape", Wandsworth Boro' News, London, 27 January 1967, p.1.

- Interchanges and connections at Verdant Lane and Jevington Way: HLG 159/959.

- Interchange at A21: "Here's the Secret M-Way Map and all the Details", Lewisham Mercury, London, 4 December 1969.

- Notes made by Wandsworth Borough Council planning officers: GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/048.

- Route study, Falconwood to Norbury, and announcement of route in July 1969; timescale of shortened consultation period: GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/054.

- Route, Norbury to Colliers Wood; early announcement of a single route to reduce uncertainty; M23 and R2 Colliers Wood-Norbury orders published in July 1969: GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/055.

- Correspondence between GLC and Bromley Council; Bromley publish line and purchase houses; GLC response: GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/059; GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/061; GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/062.

- Bromley Borough Council alternative line and interchanges: HLG 159/2183; HLG 159/2316.

- MPs addressing rallies: Michael Baily. "Experts condemn London ringway scheme." The Times, London, 23 October 1969.

- Geoffrey Manning promising to "whip up support": "Councils combine to fight M-way 'madness'", Clapham Observer, London, 11 February 1972, p.14.

- Vigars attending local meetings; letters from Streatham Conservative Association, letter from Richard Marsh MP: GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/049, GLC/DG/PTI/P/05/057.

- Ringway 2 southern section the first to be dropped by both major political parties: Hart, D. (1976). Strategic Planning in London: The Rise and Fall of the Primary Road Network. London: Pergamon.

- Newspaper report that jubilation would be "loud and long": Portavecchia, D. (1972). "The dark clouds roll away as Ringway threat is lifted". Croydon Advertiser, London, 8 September 1972.

- Section transferred to MOT as part of M23 project: MT 106/460.